Main Character Syndrome Is Killing Corporate Storytelling

On brand reverence, earned and unearned

There’s an epidemic running rampant on LinkedIn among comms and PR people. No doubt you’ve seen it, or perhaps, sadly, even been afflicted by it.

I’m speaking, of course, about the addition of “Storyteller” to what feels like half the practitioner population’s profile headlines.

There’s always been a latent vein of this in comms, but it experienced a super-spreader event in December with a Wall Street Journal piece documenting corporate America’s “storyteller” hiring spree. According to the Journal’s analysis, LinkedIn job postings mentioning “storyteller” doubled in the past year, with over 20,000 communications roles now using the term. Executives mentioned “storytelling” on earnings calls 469 times in 2025, up from just 147 a decade earlier.

Before I go further: I know. Critique of LinkedIn trends is itself a LinkedIn trend, and writing a newsletter about it is peak irony. I’m building my own narrative here while arguing that most corporate storytelling is bullshit. That tension is real, and I’ll come back to it.

But this particular trend irks me because what I’ll call Storytelling™ is rising at the same rate of consumer distrust. Something’s rotten in Denmark’s CMO office.

According to the 2025 Edelman Trust Barometer, 71% of global consumers agreed with the statement “I trust companies less than I did a year ago.” That’s a straight-up crisis.

Similarly, the Citizen Brands 2025 study found that 56% of consumers believe brands spend too much time talking about their values, up from 47% just a year earlier. More damning: 68% doubt the truth behind those claims.

University of Adelaide research found that consumers are “becoming more uncertain of brand communication due to misinformation, deep fakes, misleading claims, and perceived hypocrisy.” A majority of young people believe a brand is hiding something if it avoids certain topics.

Let me translate that from consultant-speak: people think companies are full of shit. This tracks with lived experience. If a friend tells you they “got sold a story” about something, are they speaking in a flattering way?

So yes, storytelling matters, but there’s something wrong with the stories, obviously. It’s not that audiences reject narrative inherently. Humans are wired for story. It’s that they can tell when a story is really about them versus when it’s a company admiring itself in the mirror and asking them to be voyeurs.

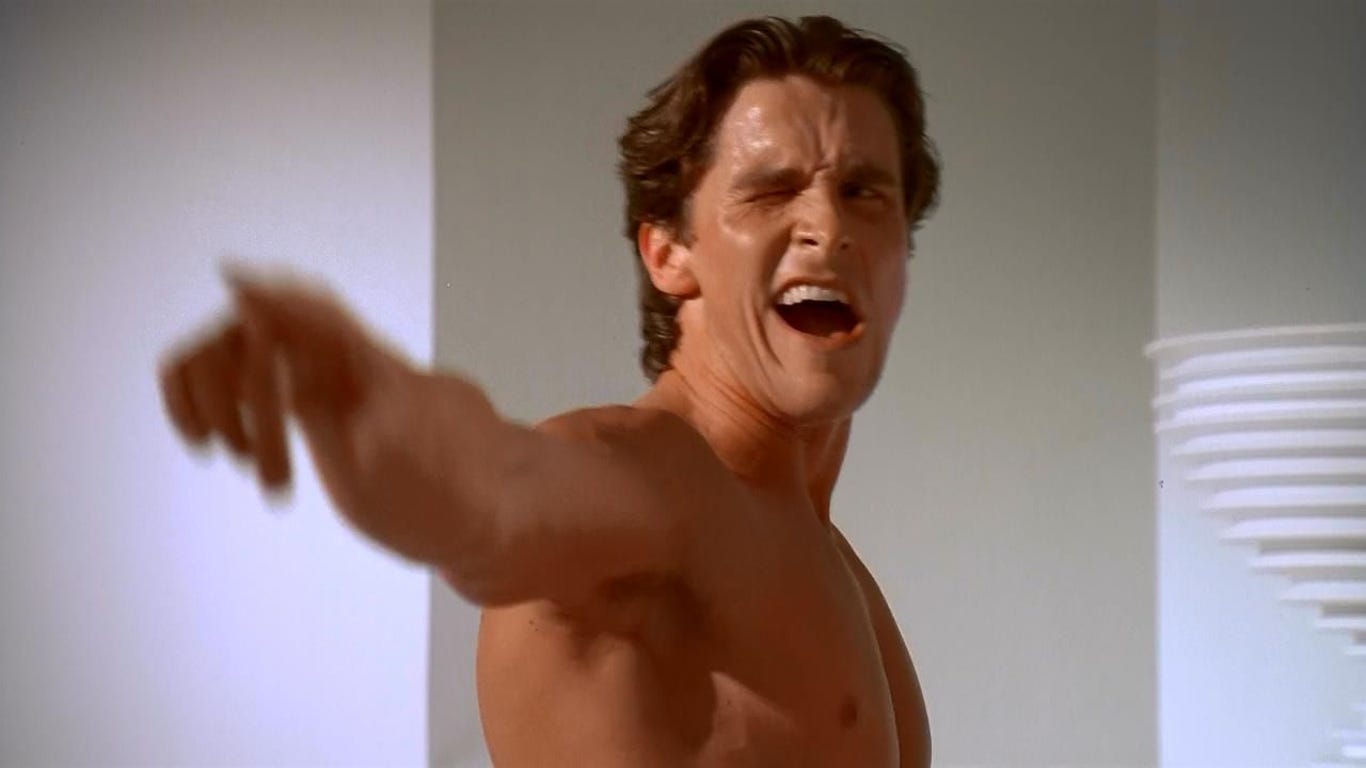

There’s a Family Guy clip from 2006 where Peter Griffin, at imminent risk of death, confesses to his family that he didn’t care for “The Godfather”. His reason? “It insists upon itself.” It’s a tight-if-confusing way of saying the movie demands reverence it hasn’t earned.1 Most corporate storytelling does the same thing.

Go back to any Storytelling 101 framework, be it Joseph Campbell’s hero’s journey, Aristotelian drama, whatever. Stories work because the protagonist is transformed through adversity. They face genuine conflict, make real sacrifices, emerge changed. The audience invests emotionally because there are actual stakes, peaks and valleys, and a reason for the audience to care.

Storytelling™ as practiced wants all of that emotional resonance without any of the vulnerability or transformation. The company is already great, has always been great, and just needs you to recognize its greatness. There’s no real conflict because conflict would mean admitting something was wrong. There’s no transformation because transformation would suggest the company wasn’t already perfect.

That’s not a story. It’s hagiography—saints’ lives written for the already converted. Audiences can smell it from a mile away. That’s what those consumer skepticism numbers are actually measuring.

But it’s not just the solipsism that grates. The dirty secret is that most corporate storytelling isn’t really for customers at all. Grand navel-gazing narratives serve VCs who need to believe they’re funding civilization-scale change. They serve executives who want to feel like protagonists in something meaningful. They serve press looking for trend pieces. They serve conference organizers booking keynote speakers. The customer is largely watching this performance and seeing through it.

Not all corporate storytelling is bad. Some companies do it brilliantly. The difference comes down to one thing: who’s the hero?

The best Apple marketing, the gold standard for tech for twenty-plus years, made you the creative, the Crazy One. They just made the tools, and the customer was always the protagonist. But most companies can’t resist main-character syndrome.

We’re living through a period where truth itself is contested territory. Political discourse has degraded trust in institutions broadly. AI is flooding the zone with synthetic content. According to Edelman’s research, 62% of respondents struggle to distinguish between truth and falsehood in media narratives.

Against this backdrop, “authentic storytelling” has become its own kind of performance. The tactics are now well-established: calculated vulnerability where brands share just enough weakness to seem relatable without revealing anything truly risky; manufactured imperfection with deliberate insertion of minor flaws to appear more human. People see through this subconsciously.

In their 2024 Red Sky Predictions, Havas Red argued that “truth telling will surpass storytelling as a key differentiator for brands.” I’d put it slightly differently: the issue isn’t story versus truth. It’s that truth has to be the foundation of the story, not a coat of paint over self-congratulation. And the first truth most companies need to accept is that they’re not the protagonist.

If you’re an in-house comms professional or an agency lead, here’s the framework that distinguishes good storytelling from performative bullshit.

Make your customer the protagonist. Every piece of content should answer: How does this make the customer the hero of their own story? If your answer is “It shows how great our company is,” just start over.

Embrace real trade-offs. If you can’t point to a specific limitation or challenge, you’re probably not being honest enough. Not enough tension. You should be able to identify hinge points in the story where you take a very different path.

Default to specificity. Vague aspirational language (“driving positive change,” “empowering communities”) is the refuge of companies with nothing substantive to say. Specific details, numbers, and commitments are harder to fake.

Test for authentic action. Before publishing any values-based message, ask: What are we actually doing about this? If the answer is “Just this post,” don’t post it. Your actions must precede and exceed your words. The research is clear: performative allies perform no better than companies that stay silent, and in many cases worse.

Most companies aren’t doing anything interesting or sexy enough to support an HBS-case-study-quality narrative. That’s fine. Most companies and brands don’t need to be centered in epic tales in order to be effective at driving business. They need to clearly explain what they do, who it’s for, and why it matters.2 They need to tell the truth about their products and services, including the parts that aren’t perfect. They need to cede the spotlight to the customers whose problems they’re solving.

None of this is as sexy as “Chief Storytelling Officer3.” It won’t generate keynote invitations or LinkedIn engagement or admiring profiles. But it builds something more durable: trust.

Wrong.

Honestly, this kind of spartan approach can become a brand story in and of itself. Witness Kirkland Signature.

Fantastic piece on the protagonist problem in corporate narratives. The trust erosion stats combined with the "storyteller" hiring surge is such a telling paradox. I've seen this play out in tech launches where the message is basically "we're changing the world" but there's no genuine conflict or transformation, just self-congratulatory vibes. The point about Apple making *you* the creative one is chef's kiss - they sold tools, not mythology about themselves. Most brands could learn alot from just being useful instead of trying to be epic.

Nailed it! I especially love this timeless wisdom: "Your actions must precede and exceed your words."